Towards a safer digital space for minors: lessons from ECAT’s research workshop

On 12 November 2025, Garance Denner, project manager within the Chair on Online Content Moderation, attended a highly informative research workshop organized by the European Centre for Algorithmic Transparency (ECAT). The event focused on the systemic risks to minors’ mental and physical health, a specific category of systemic risk recognized under Article 34 of the Digital Services Act (DSA).

The DSA is a landmark EU regulation that aims to create a safer digital space and protect fundamental rights by placing obligations on online platforms. Specifically, Very Large Online Platforms (VLOPs) and Very Large Online Search Engines (VLOSEs) are required to identify, analyze, and mitigate foreseeable systemic risks stemming from the design or the functioning of their services. Risks related to the negative effects on minors' mental and physical well-being are explicitly included as a key area of concern under this instrument.

The ECAT workshop echoed the conference organized by the French Digital Services Coordinator (DSCs), Arcom, on 25 September 2025. While the Arcom event raised important questions, it did not offer a significant platform to young people to express themselves. ECAT took a different approach: the day began with their voices, their data, and above all, their critical perspective, to then dive into expert analysis, with seven panels dedicated to a variety of perspectives related to the protection of minors online.

Giving young people a voice: a critical perspective too often overlooked

The workshop opened with a powerful reminder of the importance of giving young people a voice. With the aim of anchoring the research workshop’s discussions in the lived experience of young people, eight students from the Colegio Internacional de Sevilla de San Francisco de Paula presented the results of a study conducted among 93 adolescents aged 13 to 15. Their findings provided valuable insights into their digital habits, but also into their ability to critically assess their own results.

Their warning, “don’t believe the data because reality is different”, instantly caught the audience’s attention. This statement was particularly striking as it followed a key finding from their own survey, which showed that 70 to 78% of the respondents reported they did not feel exposed to online dangers. However, their subsequent comments and detailed analysis highlighted a sharp perception gap. The reality of exposure to online risks is, in fact, very high, as the specific data from the survey demonstrated: 44% of students declared having already accessed pornographic content and one-third estimated that their screen time is detrimental to their health. It is this contrast between a general feeling of safety and the real, frequent exposure to danger that led the authors to conclude that the students' optimistic perception is misleading regarding the reality of online risks.

Cyberbullying, addiction, and the impact of beauty filters on self-image were among their main concerns. They criticized the slow response of moderators, the lack of platforms’ investment in protecting minors, and the injustice of business models built around young users’ addiction. They also mocked the overly alarmist narratives, pointing out how adults frequently portray younger generations as less intelligent or less capable due to the impact of social media.

This intervention made one point clear: without youth testimonies, our understanding of online risks remains incomplete. Including young people enriches our analysis and provides crucial insight into their perception of online risks, reveals their real needs, and exposes gaps between institutional discourse and lived experiences.

Navigating complexity: why the online risks faced by minors require diverse, interdisciplinary insights

Fifteen speakers from a wide range of Member States (Austria, Denmark, Germany, Ireland, Italy, the Netherlands, Norway, Spain, and the United Kingdom) contributed to the workshop. This geographical diversity was crucial for effectively comparing social media use, national policies, and major risks across different EU countries. For example, Snapchat, especially its AI tools, is widely used by minors in Germany but the platform is barely used in Spain, as also confirmed by the survey at the Colegio Internacional de Sevilla, which showed 0% usage. Participants also discussed national measures, such as the smartphone ban adopted by 116 UK schools. For instance, Professor Lisa Henderson’s research, which explores the relationship between smartphones’ use and young people’s mental health and evaluates specific policies like school bans, highlighted the mixed evidence surrounding such restrictive measures. Her work demonstrated that while high screen time, particularly late at night, negatively impacts sleep (a potential causal marker for poor mental health), school bans are not a miracle solution. Rather than casually reducing behavioral problems or improving mental health, strict policies often lead to a spike in reported disciplinary infractions (e.g., school policy violations or possession) simply due to tighter surveillance and higher detection rates of behaviors that were previously overlooked. This suggests that the ban creates a new category of reported incidents without solving the underlying causes of student distress. All these exchanges highlighted the importance of a nuanced understanding, conducive to mutual learning between countries.

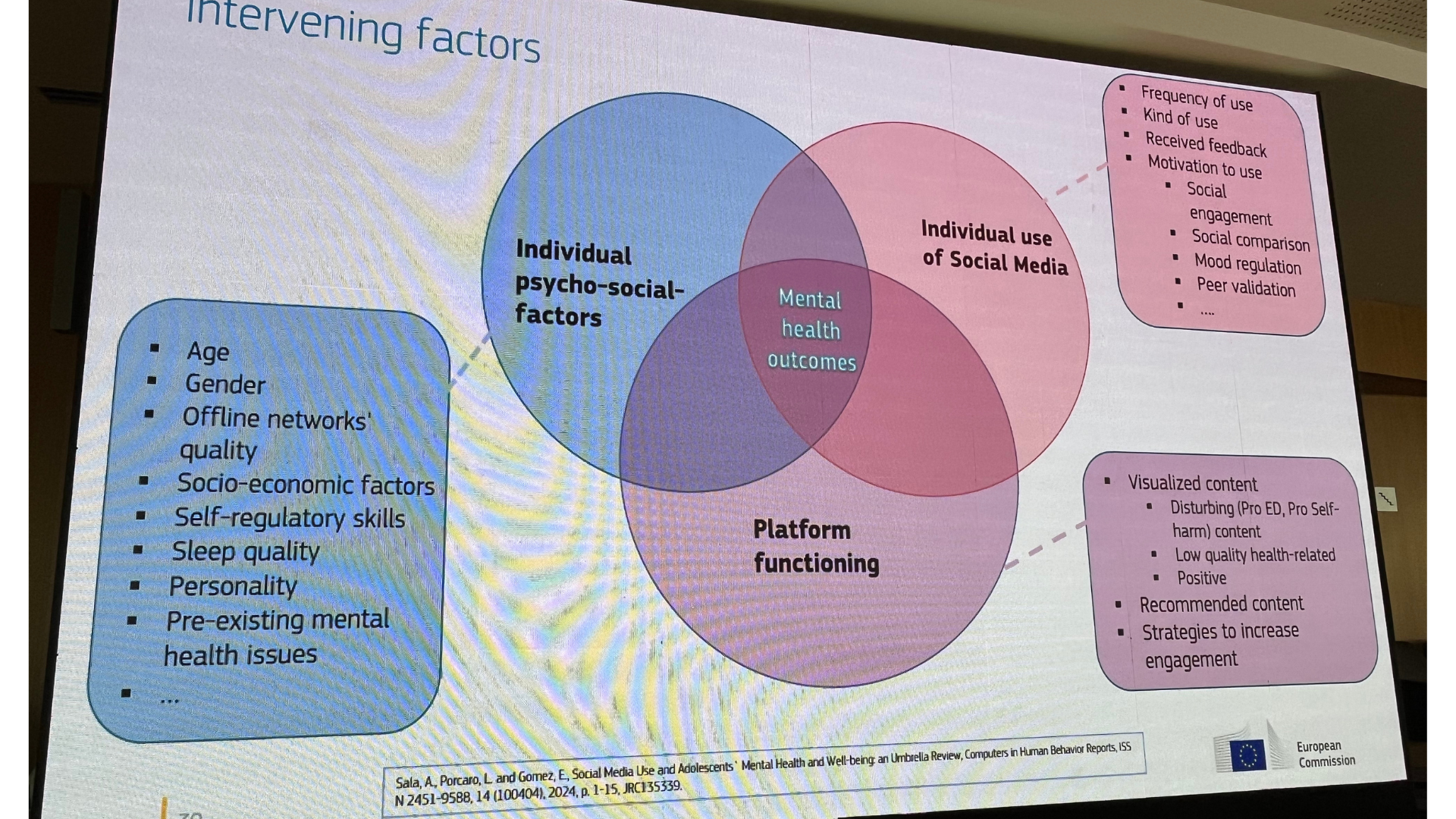

Furthermore, the workshop’s interdisciplinary approach brought a diversity of expertise to the table. The speakers represented a broad spectrum of fields, including computer engineers, communication science specialists, sociologists, neuroscientists, psychologists, regulators, and addiction experts. Their combined approaches were helpful to address an inherently multi-causal subject. As Dr. Yves Punie (Deputy Head of ECAT) also pointed out, the mental health outcome of social media usage results from the simultaneous interaction of three dimensions: individual psychosocial factors (age, gender, quality of offline relationships, socio-economic context, sleep, personality, mental health history), platform-specific mechanisms (content, recommendation algorithms, engagement strategies) and individual usage (frequency, types of activities, feedback received, motivations).

The effects on mental health were therefore multidimensional and multidirectional and could not be reduced to a single factor. These observations echoed the debates that followed Jonathan Haidt’s presentation at the Arcom event, and the criticism levelled at what was considered an overly simplistic or alarmist interpretation of the effects of social media on young people. This complexity highlighted the need for resolutely interdisciplinary research and reinforced the urgency of a comprehensive, coordinated, and holistic response.

Towards holistic solutions: cooperation, education and empowerment

The workshop yielded unanimous support for a set of solutions, fundamentally challenging overly restrictive approaches. Crucially, a complete ban of social media is widely perceived as undesirable and ineffective, precisely because research, such as that presented on UK school policies, suggests such restrictive measures fail to provide long-term improvement in mental health or a reduction in high-risk incidents. The main conclusion that emerged was that the first and most effective solution resides within the platforms themselves. This requires platforms to strengthen their responsibility through design changes. This core recommendation is powerfully aligned with the outcomes of the Arcom event, establishing a broad consensus among researchers and regulators. Specifically, there was agreement on the need for platforms to offer settings that better protect young people’s mental health. Studies showed that healthier design choices, such as pagination, implementing ‘explicit play’ (stopping content flow until the user actively decides to continue, as opposed to autoplay), or offering non-personalized feeds, would enable minors to better control their screen time and, in many cases, significantly reduce it. This focus on platform design was complemented by a consensus on the parallel need to strengthen age verification systems.

However, faced with the persistent inaction of platforms and the difficulty of imposing these measures on them, experts have proposed innovative solutions. These would include creating smartphone-free zones, particularly in schools and sometimes even in certain areas of the home, or developing more virtuous alternative platforms, akin to ‘organic’ products in supermarkets. These ‘organic’ platforms would be fundamentally different from mainstream services by prioritizing user well-being over engagement metrics and data harvesting. They would incorporate ethical design principles such as the design features cited below. Yet this solution comes with a challenge: like organic goods, these ‘organic’ platforms could be more expensive and therefore inaccessible to many families, ultimately benefiting only the wealthiest.

Another widely discussed point, which echoed the debates at the Arcom conference, was the need for a significant effort to educate people and raise awareness about digital technology: the more informed and aware individuals are of online risks, the better they can protect themselves. The goal is therefore to strengthen genuine collective resilience in the face of platforms. Speakers emphasized the importance of digital education at all ages, particularly the upskilling of parents, teachers, and trusted adults. Indeed, many of the studies presented at the workshop highlighted the sentiment of fear or shame that often prevents minors from confiding in adults: as they fear punishment, disappointment, or simply lack safe spaces to express themselves they often fail to report or share the risks they are confronted with in the online space. Parents, for their part, often feel overwhelmed, lack knowledge, and institutions sometimes seem inaccessible. One U.S. study by Common Sense Media (2025) even showed that a third of the young people who were surveyed would sometimes rather talk to AI tools rather than to their parents or teachers for important or serious conversations, due to their non-judgmental approach. This highlights the importance of non-punitive mediation, improved parental digital literacy, and collective efforts to re-establish dialogue.

Conclusion

The ECAT research workshop on the DSA’s systemic risks to minors made one thing clear: building safer online space requires a coordinated, multi-face strategy that directly confronts the complexity of the challenge.

This pursuit of safety must begin with empowerment. The powerful intervention by the Seville students underscored that effective risk analysis is impossible without centering on the voices, critical perspectives, and lived experiences of young people.

The core findings of the day converged on three main pillars to guide future action. The primary solution resides with VLOPs, which must fulfill their DSA obligations by moving away from addictive business models and implementing “well-being first” design choices. Achieving genuine, evidence-based solutions requires a resolutely interdisciplinary approach to understand the complex, multi-causal interaction of platform design, individual factors, and usage patterns. Ultimately, the effectiveness of both regulation and design hinges on widespread digital literacy and building collective resilience through education and open dialogue among minors, parents, and trusted adults. Moving forward, it is necessary to combine evidence, education, and genuine accountability to match the complexity of the online risks minors face.